Author | M. Martínez Euklidiadas

The number of medical apps available for patients has increased in recent years, together with other health care apps aimed at users. From medical and health encyclopedias to videoconference software to communicate with health centers and even apps to record the medication patients take, there is no doubt that mobile devices are an interesting healthcare tool.

The COVID-19 pandemic has disrupted healthcare around the world, leading to a digital healthcare transformation, with health apps for patients emerging as an important pillar in the new concept of healthcare systems.

What is the purpose of medical apps for patients?

Patients around the world have installed health apps on their devices through their private insurance. Mainly for data protection and security reasons, but also due to a certain degree of inertia and lack of direct competition, public healthcare systems have barely ventured into the app sector, straggling behind and solely making use of telephone consultations.

These apps enable patients to make appointments or have video consultations with doctors in an easy and intuitive manner. These two functions are the most commonly used, but there are others, such as rescheduling appointments, requesting medicine changes, accessing medication on their healthcare card, establishing reminders and renewing policies.

In addition to these native apps, there are more populated third-party apps in which the user is not the client, but the service user. They include a whole host of useful features such as medication reminders, symptom journals, healthy lifestyle tips or weight control trackers.

Can health apps help relieve healthcare centers?

Particularly as this historical moment of the pandemic unfolds in which it is not advisable for people to congregate in enclosed spaces, relieving the number of patients in healthcare centers is wise. Particularly in cities located in countries with __low numbers of healthcare centers and high medical care figure__s, which is the case in developing countries.

That is why countries around the world are choosing to prioritize video consultations with primary care and non-urgent patients. Most of these consultations can be resolved without having to visit the health centers, which not only relieves the health center and prevents infection, but it also has a positive effect in terms of reducing greenhouse gas emissions or saving patient travel time.

Disease diagnosis and monitoring apps

In addition to those described above, there are also specific disease diagnosis and monitoring apps. Although these fall into the category of medical apps for patients, healthcare staff often have to use them or they play a fundamental role in the process.

Apps to manage type 1 and type 2 diabetes are common. These tools connect to the glucose monitor via Bluetooth and, by combining the data with others such what the user plans to eat throughout the day, they can inform the insulin pump of how many units are required at the precise time. They can be used directly by patients after just a short period of practice.

There are other innovative apps such as those capable of detecting melanomas (a type of skin cancer) with the use of photographs. With the arrival of COVID-19, this form of support for medical diagnosis has become more popular, however, it is important to emphasize that, even with tools based on artificial intelligence, a medical professional will be the person who analyzes the information and confirms the validity of the photographs or the diagnosis.

Security concerns: Where are my data stored and who holds them?

There has been intense debate regarding electronic health record systems, particularly in Europe, given the legal certainty on privacy safeguards offered to patients regarding their data. In recent years, the number of cyberattacks against all sorts of databases has risen, and the health data of patients are highly sought after by criminals.

However, even within a completely legal circuit, the processing of these vulnerable data is controversial. As Cathy O’Neil reveals in ‘Weapons of math destruction’, the data market can affect uses in ways that are hard to see. And medical data are particularly delicate and potentially harmful. An example:

You use a free app for a few years to make sure you do not forget to take your medication, some of which reveal a deteriorated health status. When, at a later date, you decide to take out health insurance, the price is staggering.

Unknowingly, that app you were using sold data to third parties, which included your insurance company.

Even though there are now specific laws in place to keep health records safe —for example, genetic discrimination is now illegal in the United States— the reality is that it is rather hard as a user and customer to trace the information or to understand how your data are being used by third-party companies.

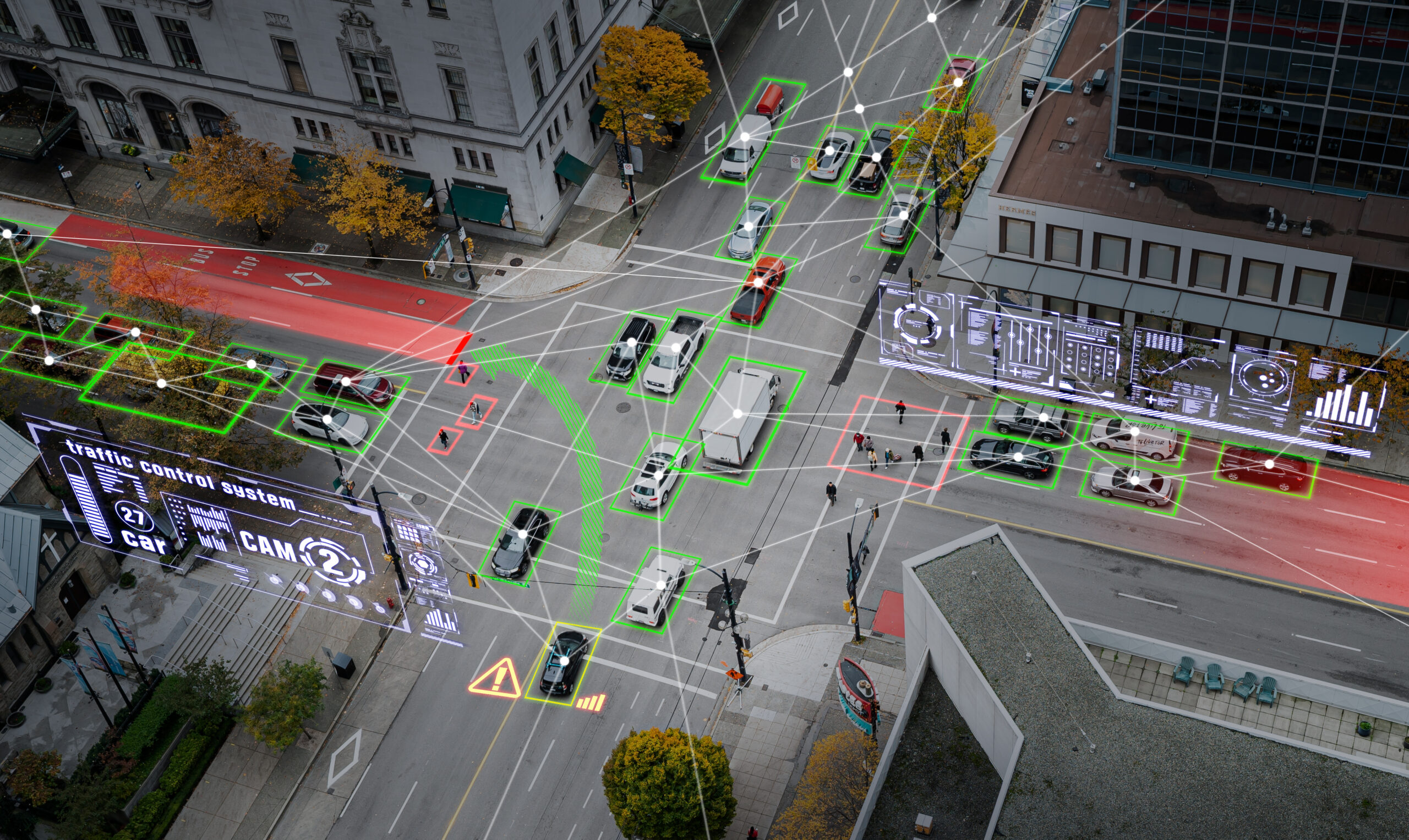

The digitalization of medicine, which is also related to innovation in hospitals and the experience of smart regions in this area, will be gradual. To date, this digitalization has been extended to the easiest areas: private primary care and mobile apps. But soon we will see them in many other areas of our city.

Images | iStock/DragonImages, iStock/Lacheev, iStock/nensuria