Author | M. Martínez EuklidiadasLondon has been at the forefront of innovation for hundreds of years. Christened with the name of Londinium by the Romans in AD 43, this enclave has never stopped being abuzz with activities and diseases. As a result, London was ravaged by epidemics. From cholera to industrial pollution or the plague, the city became resilient.Without the epidemics caused by hundreds of thousands of people overcrowding the city, we would not be able to read Shakespeare. Perhaps the Industrial Revolution would not have taken place in London and epidemiology would have emerged in a different city. London was able to learn from the infectious diseases that ravaged the city and it came out stronger.

From cholera to epidemiology

One million two hundred thousand people lived in the city. The Romans had introduced the cobbled streets two centuries earlier, but it was the 2nd century, and at the northern end of the Empire, hygiene practices were much more lenient than those inherited from Ancient Greece by the Romans. London did not have a sewerage system. Diseases were rife. It comes as no surprise that the city went through a series of flus, generalized pneumonias, a constant succession of smallpox, typhus, tuberculosis, polio and any other infectious diseases that one can imagine.Although the efforts to create a sewerage system greatly improved the quality of life of residents, the epidemics did not disappear. It was in 1854, when the young doctor, John Snow, came up with the idea of drawing a map of the people dying of cholera in a neighborhood. That experience identified the public water pump in Broad Street as the cause of the outbreak. Epidemiology had begun, a discipline that we owe so much to now during the coronavirus crisis that will define our cities.That well was closed and that outbreak was alleviated. But one of the most serious outbreaks occurred in 1814 in the midst of the industrial revolution. London was burning, and we are not referring to its frequent fires. The city was breathing coal. Factories had chimneys, ships had chimneys, trains had chimneys. If it had an engine, it had a chimney.In 1814, coal consumption in London had reached 15 million tons a year, and that summer became known as ‘The Great Smog’. In 1840, a thick yellow fog smothered the city like a blanket and in 1880, there were on average 60 fogs throughout the year. There was even a great smog more recently in 1952, with 12,000 deaths. People were suffocating. The city was slow to respond.London generated more smog during the 19th century than any other city by far. Paintings from the period illustrate landscapes without a sky. In Constable’s oil painting ‘Hampstead Heath’, there is barely any blue sky.But it was also one of the first cities to respond to the studies that related chimneys with respiratory diseases. It is currently one of the cities with the best quality of life, according to the BCG and The Network study ‘Decoding Digital Talent 2019’. The road has not been easy. Innovation has been constant.

Getting water to homes, the first great invention

We have the Dutch engineer, Peter Morice, to thank for one of the most original systems of the time. He designed and built an immense wheel-driven hydraulic system on London Bridge to supply the city with running water. It was 1582, and hundreds of London homes had access to water thanks to this system, which continued to grow until 1702.However, that was in no way the panacea. In fact, access to ‘drinking’ water caused the city to grow without limits which, in turn, led to cholera infections, the plague and fires. All of these were unprecedented in terms of scale. Cholera still prevails in a large part of the world today.

The Great Plague, the Great Fire, the Great Smog, the Great Stink

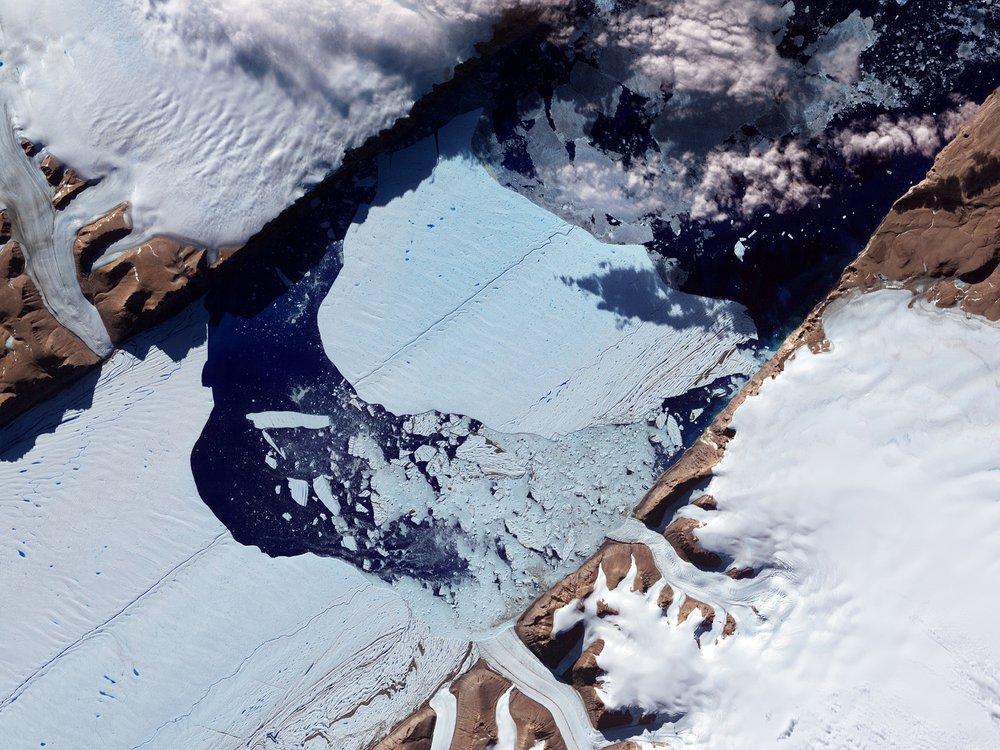

London had been experiencing, together with its respective diseases, ‘small stinks’ since the Middle Ages when its minute and notably insufficient sewerage network was designed. But in 1858, the stink (miasma) was unbearable. During that period it was extremely hard to stomach the smell in London, the city that made holding handkerchiefs dipped in perfume to the nose popular to bear the rotting smell of its river.A river that was used as a giant sewer until well into the 19th century. It was normal to see the Thames full of rotting animal corpses, waste water and even dead bodies (clearly it was cheaper than a burial), but the stone pavements, if they existed, were not much cleaner.The heat was unbearable in 1858. Something had to be done. People would pass out when they went near the river. The House of Commons, at last, made a decision. With John Snow, and the engineer Joseph Bazalgette at the helm, London began a series of public works, building what would be the largest sewerage system in the world. This was the first time something of this scale had been attempted. The aim? To eradicate diseases and epidemics.

London’s sewerage system: goodbye to the stench and infectious diseases?

Bazalgette’s solution was ingenious. He built major brick-lined sewerage systems totaling over 100 kilometers in length, plus around 2,000 kilometers of secondary pipelines. He visited the densest part of London to calculate the section, calculating the diameter needed to evacuate the waste water from the residents and then generously multiplied the diameter a number of times by two.This oversizing of the sewerage system was so vast (the area and, therefore, the flow, increase with the diameter squared) that London still uses these pipelines today in many areas. Although the direct consequence of the project was that it was not finished until 1875, decades in which cholera continued to obliterate the city.

Florence Nightingale: infrastructure is not enough

1860 was a decade that saw unprecedented scientific advances. While thousands of men were laying the new pipes, another small army, this time made up of women, was looking after the sick in hospitals. And St. Thomas’ Hospital had an enormous impact thanks to the figure of Florence Nightingale.During her experiences as a nurse during the Crimean War in 1854, Florence discovered, learned and taught the importance of hygiene practices in nursing and medicine in general. The same year in which Snow discovered the cholera well using a map, Florence discovered that hygiene and ventilation greatly improved the health of sick patients.On her return, she introduced some key improvements in St. Thomas’, convincing the Royal Commission to improve ventilation in hospitals, adding drains or frequently cleaning surfaces. It was a resounding success, as we now know.

The new Tideway project

Monumental projects had eradicated the Great Stink, but in 1960, London continued to be one of the most contaminated cities in the world. In 1957 the Thames was declared ‘biologically dead’ by researchers at the Natural History Museum. It was “an open sewer”. The bombing raids during the Second World War had destroyed a large part of Bazalgette’s work and environmental awareness was growing.In 2012, London approved the Tideway project to extend and improve the infrastructure of the sewers with the help of the company Bazalgette Tunnel Limited. Just in time, in fact. In 2013 the first fatberg was discovered, a 15-ton mass of fat and wet wipes. A clot in the veins of Bazalgette’s brickwork. In 2017, a 150-ton fatberg was discovered.It is clear that there is still a great deal of work to be done in terms of cities and health. In 2020, an almost perfect correlation has been identified between sewers testing positive for COVID-19 and local hospitals filling up one week later. Big Data continues to make progress, hygiene practices too, Therefore, the very least cities can do is use these advances, as London did after centuries of epidemics, to come out stronger.Images | iStock/curiousufo, John Snow, John Constable, Peter Morice, Wellcome Images, Marcos Martínez