Authors | Arantxa Herranz, Elvira Esparza

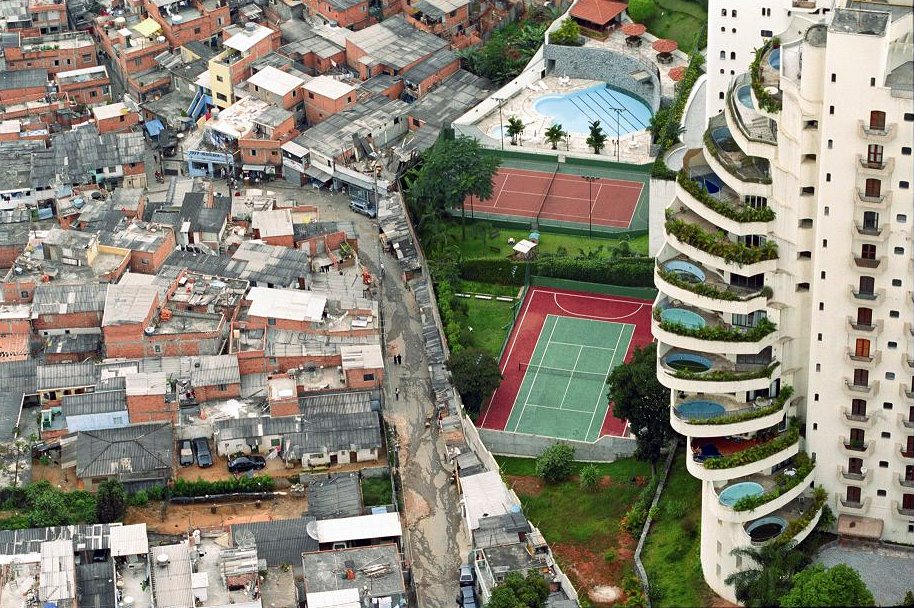

Although it is not easy to accurately measure or track the population living in informal settlements, the latest 2022 census by the Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics (IBGE) estimates that more than 16.3 million Brazilians (8.1% of the total population) live in the 12,348 favelas spread across the country. São Paulo is the economic and financial heart of Brazil, but it is also the state with the highest number of people living in informal settlements, specifically 3.6 million people. Paraisópolis is one of these neighborhoods.

NASA itself explains how, through photographs taken by its satellites, the growth of this large urban area can be observed. The most notable change that can be observed from NASA’s photographs is the spread of the suburbs, where growth has been fastest. Over the last decade, the inhabitants living in shanty towns in São Paulo reached 1.7 million compared with the 800,000 living in the city centre during the same period, which doesn’t point towards a particularly sustainable development.

WHAT IS PARAISÓPOLIS?

Paraisópolis, covering an area of 332 km2, is the second largest favela in Sao Paulo and the fifth in Brazil. It is also one of the first places where efforts to improve the quality of life in favelas were implemented.

Paraisópolis shows how extreme poverty and wealth can be separated by just a couple of streets, since it is next to the Morumbi neighborhood, one of the most exclusive areas of the city.

In 2021 it celebrated its first centennial anniversary, as its origins date back to 1921, when the Morumbi Estate, dedicated to tea cultivation, was divided into 2200 lots by União Mútua Companhia Construtora e Crédito Popular SA to create a luxury development. However, this infrastructure was never built, so the land was left abandoned and was occupied by low income families arriving in the city from the northwest of Brazil to work in construction.

Over time, this settlement grew with the arrival of residents from other favelas in the city that had been removed. Due to the lack of urban planning, Paraisópolis grew as a favela characterized by narrow and steep streets, without sanitation or basic services.

However, Paraisópolis has evolved and has become an example of how the quality of life of its residents can be transformed by seeking solutions to all the challenges posed by a settlement of this size.

THE GROWTH OF FAVELAS: THE MARGINALISATION PROBLEM

Much of the suburban growth took place in favelas, which emerged when people built their homes on the steep hillsides in areas that were unoccupied as they were deemed inappropriate for construction. An estimated 20 to 30 per cent of São Paulo’s population lives in favelas, which poses a challenge for the municipal government because these unplanned communities often lack connections to the basic sewage, water and electricity services.

Favelas are shanty towns in Brazil. Many people in these places have basic-salary jobs and, therefore, low incomes. These jobs tend to have irregular shifts and various work locations. This makes it even more difficult to collect accurate data to help with town-planning.

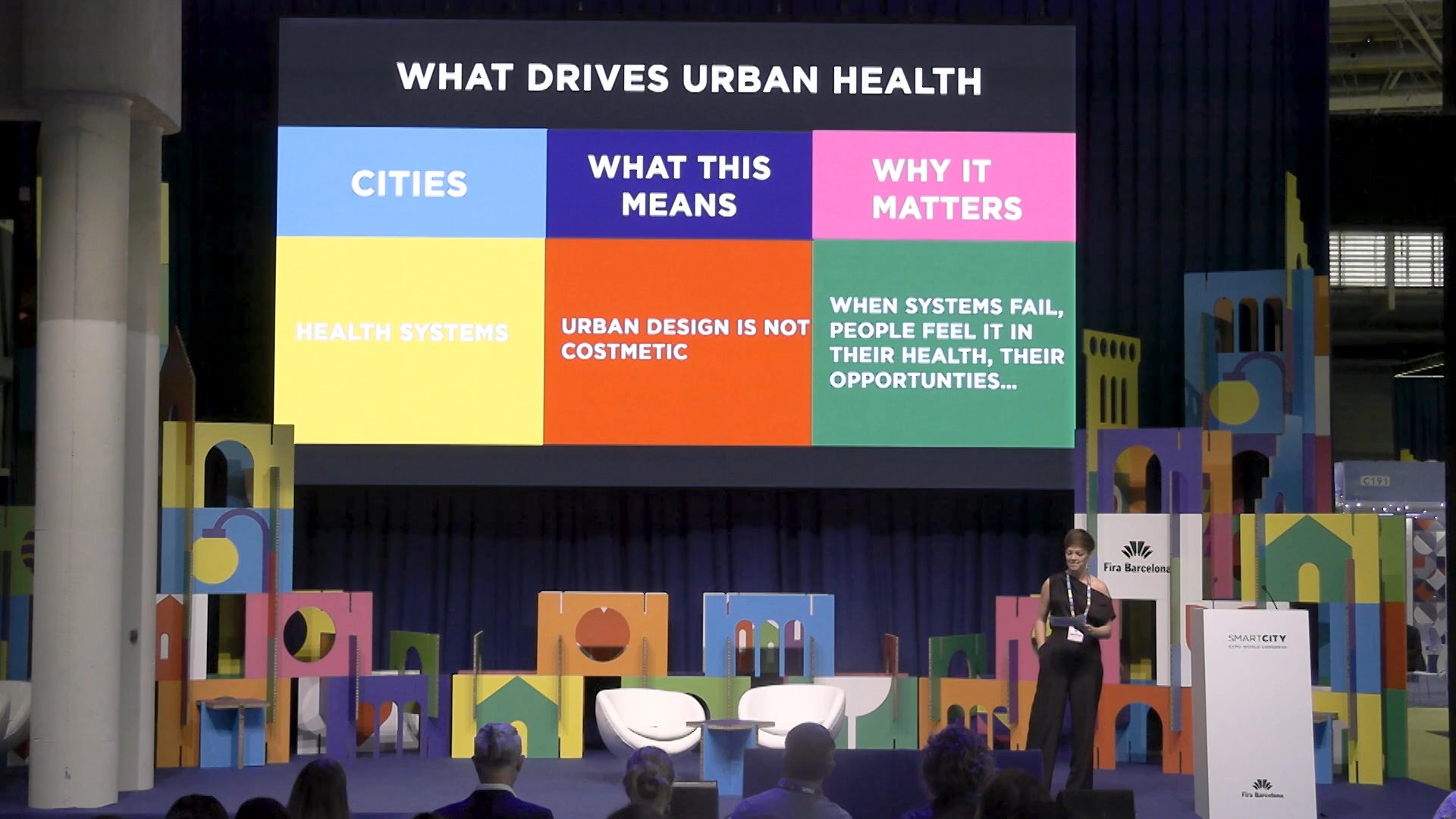

The problem with these slums is that their urban housing conditions tend to be so hard that they are declared “intolerable” by the United Nations itself. Insecurity, lack of basic services (particularly water and sewage), inadequate and unsafe construction structures, overcrowding, location in dangerous areas and high concentrations of poverty, as well as social and economic deprivation, broken families, unemployment, economic, physical and social exclusion are just some of the characteristics of these shanty towns.

This, in turn, results in the inhabitants of these areas having limited access to credit and to the formal job market due to stigmatization, discrimination and geographic isolation. Their inhabitants are more likely to suffer water-related diseases such as typhus and cholera and HIV/AIDS.

PLAN FOR URBAN AND SOCIAL DEVELOPMENT

As a result of these circumstances, numerous governments decided to demolish these neighborhoods as a way of eradicating all the problems associated with them. However, in 1980, Brazil decided to improve the quality of life in these shanty towns instead of demolishing them. The idea is that it is not just more humane to integrate the shanty towns into cities’ activities, but it would also be more economically beneficial than excluding them.

One of São Paulo’s objectives is to take electricity sewage systems and drinking water to as many areas as possible. Furthermore, they are promoting a kind of “home exchange” program: when a family abandons a shack to go to an apartment built by the government, a new family from a worse area can move into that shack until a better solution can found.

The experience gained also enabled a national “City statute” to be established in 2001, which establishes that cities must have master plans in place for these shanty towns. This document also outlines a series of tools that can be used by municipalities, such as allowing cities to create “areas of special interest” for disorganized shanty towns, formally recognizing them and classifying them for social services.

This City Statute is supported by Cities Alliance, a global partnership made up of national and local governments, UN-habitat and the World Bank, focused on extending solutions to combat urban poverty. One of the first measures is to always guarantee that settlements have access to running water and sewage services.

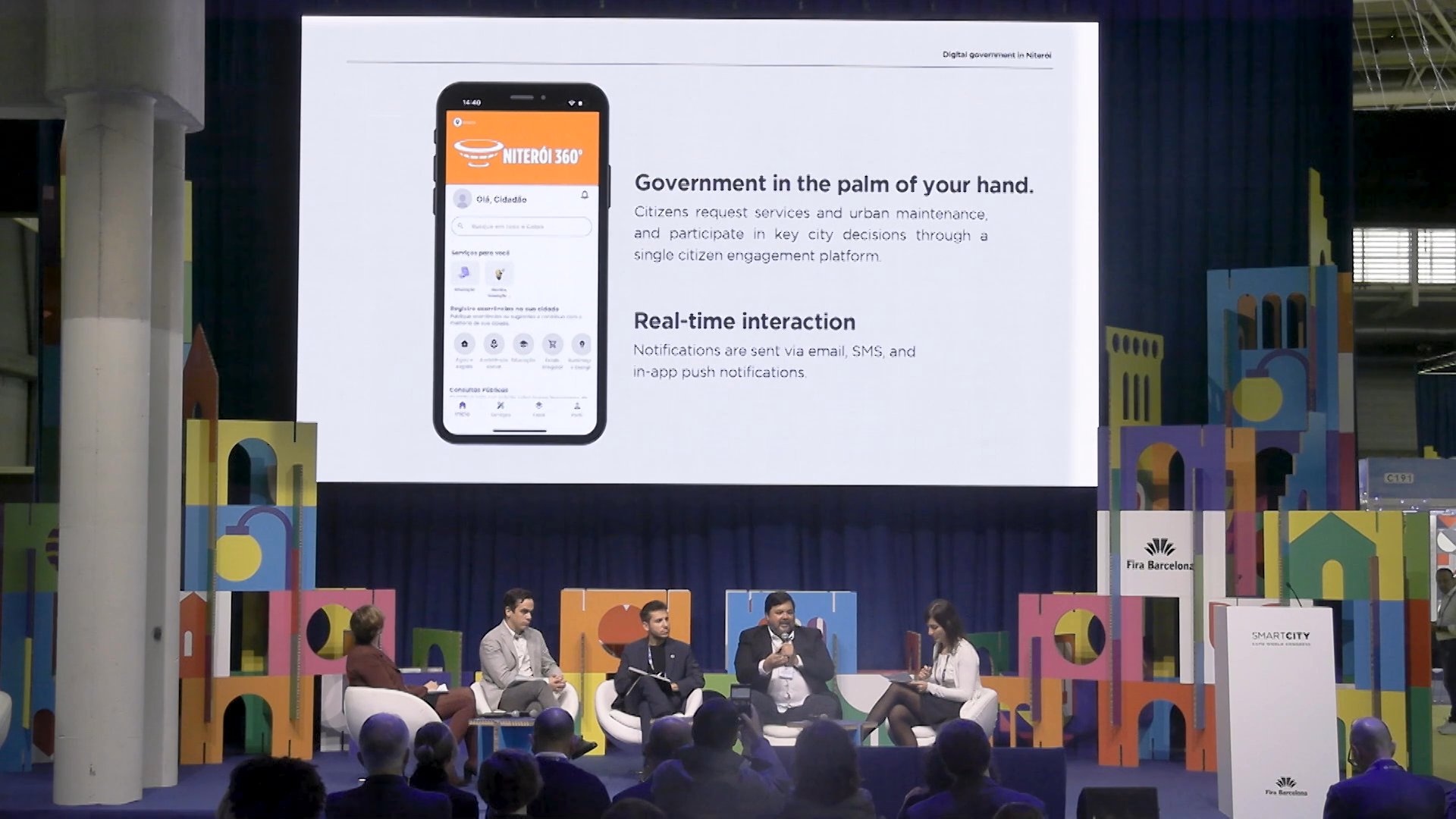

In 2006, the city of São Paulo also introduced an information system which enables it to know the condition of the shanty towns or areas in danger of flooding, so the cleaning and maintenance services in the city can be managed more efficiently.

DATA SHOWING THE CHANGE IN PARAISÓPOLIS

The changes and transformation of Paraisópolis are evident and can be measured with data. Currently, according to the latest census, the city has around 21,000 registered residents, although other sources place the population between 80,000 and 100,000 people. Thirty one percent of the population is made up of young people between 15 and 29 years old, and women are the heads of household in 42% of homes.

Almost 84% of households have access to a sewage system, and 48% of households have adequate urban infrastructure, meaning they have drainage, sidewalks, and paved streets. It also has public schools, health centers, and cultural centers, and infrastructure projects are underway to channel streams and build reservoirs to prevent flooding in the most vulnerable areas, as well as the construction of safer housing with adequate infrastructure.

In addition, through G10 Favelas, a group made up of leaders and entrepreneurs from the ten largest favelas in Brazil, Paraisópolis has launched several initiatives to become a sustainable and accessible city.

Together with Green Mining, it has created the Factory Price Station, a circular economy project for waste collection and recycling aimed at keeping the streets free of trash. The goal is to raise awareness about the importance of recycling. To achieve this, recyclable materials are purchased from residents at a fair price to show that waste has value. This initiative promotes environmental education and community engagement.

Urban garden projects have also been developed to reduce environmental impacts and improve the quality of life of favela residents. In addition, entrepreneurship has been encouraged to improve the employment rate in the favela, which previously depended heavily on domestic work in the Morumbi neighborhood. Support for entrepreneurs also aims to facilitate business partnerships with external companies and attract investment to the favelas.

Paraisópolis therefore shows that certain measures can be applied even under the most challenging conditions to improve the lives of its residents, while also making it easier for city authorities to better manage these more disadvantaged areas.

Images | nakagawaPROOF/Flickr (CC BY 2.0), Wikimedia, Pixabay, Alex_so/iStock