Authors | Anna Solana, Raquel C. Pico

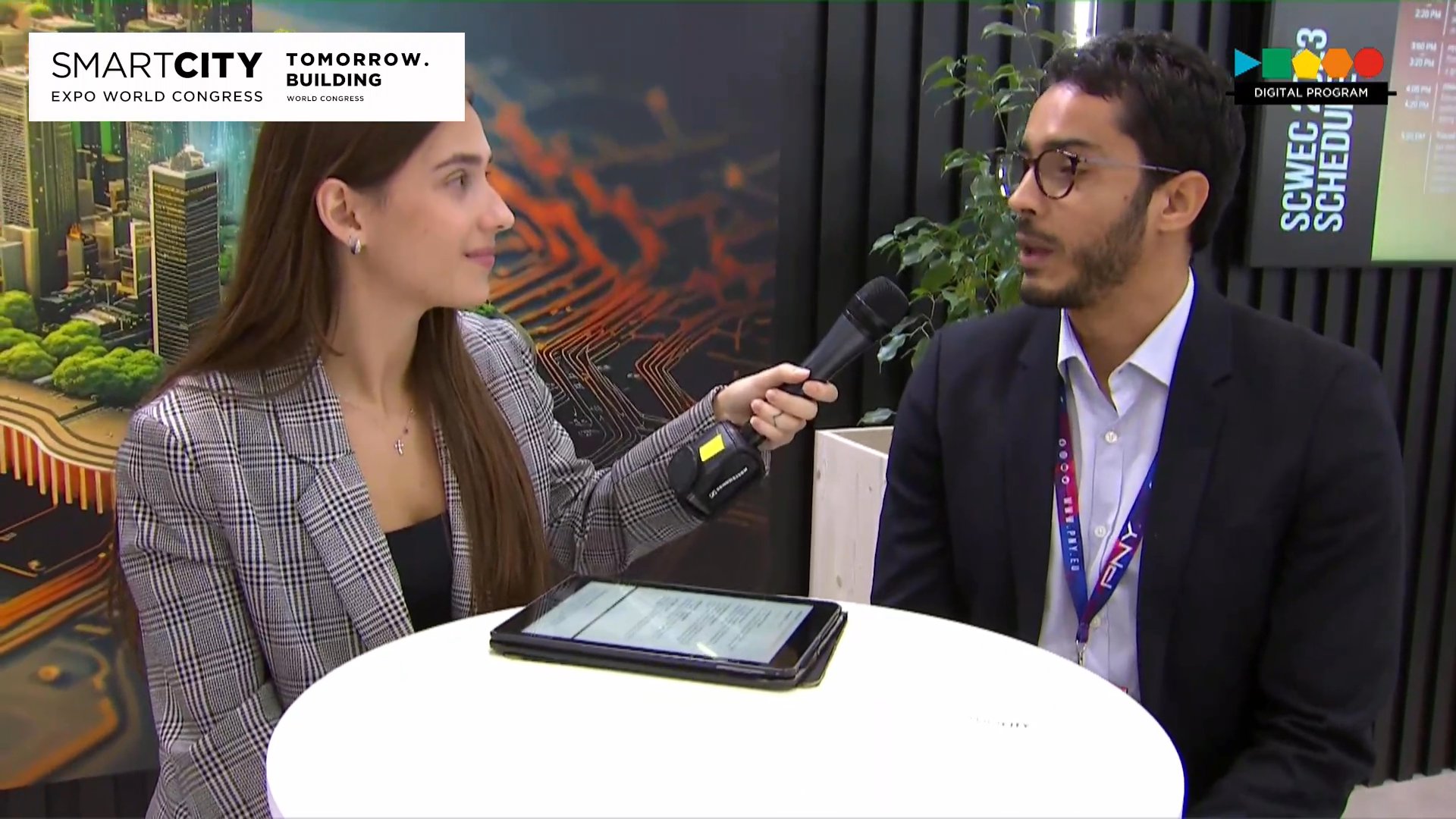

An interview with Kilian Kleinschmidt, one of the world’s leading authorities on humanitarian aid, founder of Switxboard and former manager of the largest camp for Syrian refugees.

One in every 67 people worldwide has been forced to flee their home. This shocking figure highlights the staggering number of people who have been forced to leave their places of origin.

The latest UNHCR statistics, based on July 2024 data, reveal that 122.6 million people worldwide are forcibly displaced. The agency defines forcibly displaced people as those who have had to leave their homes “due to persecution, conflict, violence, human rights violations, and events seriously disturbing public order.” Among these, 43.7 million are classified as refugees.

Increase in refugee numbers

Regardless of the reason, these are significant numbers that impact not only the countries that take them in but also, and often less visibly in the media, the cities they settle in. Similarly, it is important to recognize that the total number of displaced people has surged dramatically over the past decade. Between 1993 and 2012, the number of displaced people remained below 50 million. However, UNHCR data shows a steadily rising trend since then.

The impact of ongoing conflicts and prolonged crises helps explain these rising numbers. Violence against the Rohingya has led to the creation of the world’s largest refugee camp, while the wars in Syria and Ukraine have triggered massive population displacement.

UNHCR estimates that this conflict has left 16.7 million people “in need of humanitarian assistance and protection.” Syrian refugees have been largely displaced, especially to neighboring countries. The recent end of the Syrian civil war has not brought an immediate resolution to the refugee crisis, which the agency still considers one of the largest in the world. Some Syrian refugees have begun returning to their country voluntarily, but humanitarian organizations warn that their reintegration will pose a significant challenge. The reconstruction of Syrian cities is a crucial component of this process.

Refugee camps and urban challenges

Many displaced people settle in refugee camps, which often grow into small cities due to their sheer size and complex challenges. The camps have to create health, transport, or habitational infrastructures. They must manage large influxes of people while striving to prevent the camps from turning into ghettos. Studies indicate that these camps have inspired hybrid urban habitability models. This is why it is essential to approach these areas as urban spaces.

Similarly, refugee crises are an urban issue because, despite the tendency to establish camps in remote areas, most displaced people ultimately settle in cities. According to the World Refugee Council, 60% of refugees and 80% of displaced people live in urban areas. In fact, Cristiano d’Orsi from the University of Johannesburg explains in The Conversation that this urban presence has become a source of social and political tension in African regions hosting large numbers of refugees.

In these urban environments, refugees face uncertainty and significant challenges in accessing housing. As Romola Sanyal, professor at the London School of Economics, points out, these experiences are similar to those faced by disadvantaged urban communities. Urban management strategies and planning must take these realities into account. Sanyal explains that in Lebanon, the Syrian refugee crisis was addressed at the neighborhood level, focusing on urban areas with higher refugee populations and resolving emerging issues—ranging from improving street lighting to revitalizing parks. D’Orsi notes that a network of 150 cities worldwide has signed a declaration recognizing the rights of urban refugees.

Listening to refugee populations is crucial—not only as a matter of social equity but also because of the potential they bring to cities. It is important to remember that the growth of some cities in the 20th century was driven by the arrival of refugees and displaced populations. A report by the Royal Town Planning Institute warns that refugees are being excluded from urbanization opportunities, causing cities to miss out on potential prosperity and development. Refugees must be heard.

What does the refugee population need

In order to understand what the refugee population needs and the related challenges, we interviewed Kilian Kleinschmidt, one of the world’s leading authorities on humanitarian aid, founder of Switxboard and former manager of the largest camp for Syrian refugees. Kleinschmidt is one of the world’s leading authorities on humanitarian aid and he is convinced that technology is giving poorer people a chance to progress.

Kilian Kleinschmidt worked for 25 years for the United Nations High Commission for Refugees (UNHCR) in various camps and operations worldwide. In 2014, he started his own aid consultancy, Switxboard, a connectivity project to “democratize access to global knowhow.”

What do you look forward to most at the start of your day?

I basically try to solve logistics… I believe there’s an answer to most problems we face. Mobility is part of our world, and I try to address this issue. The reasons for displacement today are far more complex than those envisaged by the 1951 Convention.

How can we best support people who have been displaced?

People move because of extreme poverty, climate change and few as they are part of the global privileged mobility community. Thus, it’s all about getting back to basic principles. We are one world and some of us have been luckier than others. Hence, global solidarity is crucial because some have largely benefitted from the resources of others.

Do you think citizens are concerned with this particular issue in a scenario with growing inequalities in the developed world?

It’s a reality. You cannot exclude people because they are too far away. That is the price we have to pay for a globalized world. People feel afraid, and angry and compassionate at the same time. In fact, we have never had more mobilized people than now. In that sense, it’s not a bad period. Hence, we can and must try new strategies. Sustainable development goals are not a socialist fantasy. They have to be realized for all of us to survive!

In that sense, you claim that charity of the 20th century needs to be replaced with connectivity of the 21st… What do we need to turn this will into a reality?

According to the 2015 ITU report on global connectivity, the proportion of the global population covered by mobile-cellular networks is now over 95%. Still, connectivity is not perfect. So, we are just beginning to redistribute resources, with incredible technologies being developed. Africa is a perfect example. There are also some ongoing research and projects to deliver vaccines using drones. People want to take care of themselves and not to be dependent on aid. With these technologies they have a chance to progress. Connectivity and access to knowledge is the only chance to lower the divide between the rich and the poor. Likewise, the progress of the Internet of Things (IoT) is expected to impact almost every social and economic sector, including education and health. The new generation of technology, including the processing and analysis of new data, can provide a lot of opportunities if we democratize it.

Yet, people need to get access to technology and get the ability to use it. How can we promote this kind of initiative when governments think about refugee camps as temporary places?

There is a big need to change the way we look at camps. They are not storage facilities; they are living spaces. The average refugee spends 17-20 years in displacement, according to the UN. That’s a generation. Thus, we have to look at camps as living places and we have to stop looking at refugees as helpless victims. In doing that, we are also preventing these people from thinking they are living in a limbo period, waiting for something to happen. We are contributing to lessening tensions and promoting the reconstruction of societies. This situation offers opportunities for change. We need to look at camps as urban spaces and invest into structures that make that places sustainable and independent from charity aid, instead of wasting money in unsustainable initiatives. The logic will have to be a city development logic linked to social and sustainable investment and service delivery.

In 2014, you started your own aid consultancy to build up the bridge between those who have the knowledge, the technology, the financial resources, and those who don’t have them. What are the projects you are carrying up?

Switxboard is a project of ultimate global connectivity. It should become an artificial intelligence tool with a human element, able to connect resources and technologies, able to connect the world’s capacities with the world’s needs, like a humanitarian Tinder or something. We are already working in disruptive technologies such as Open Ware FabLabs, i.e. high-tech maker-spaces designed to enable refugees, startups and communities to co-create innovative solutions; or a concept called Refugee Open Cities (ROC21) to transform camps into inclusive cities, bunk bed-halls into makerspaces and emergency homes into self-sustaining living environments. These are just a couple of examples.

We have to break up with the idea that if you’re poor, it’s all only about survival. Project Switxboard will lead to the building of the world’s largest corporation without headquarters and hierarchy. The organization of the future is actually composed of millions of small units getting together when and where needed.

What kind of city/place would you like to live in in 20 years?

In a few years, 75% of the world population will live in cities. The movement towards cities is unstoppable, but most of them are not very well managed yet. So, we have to invest in better managing urban spaces as for people their village or city is more important than their State. As for me, I would like to live outside big cities and visit them just from time to time.

Can a congress like SCEWC help develop smarter and resilient cities able to cope with crisis?

Walking around SCEWC and seeing smart technologies is great and mindboggling, but I would focus on management and inclusive participation. In fact, I think it is crucial not to think about smartness only in technological terms.

Images | SH Saw Myint/Unsplash, Kilian Kleinschmidt, Networker Global and Switxboard founder.