Authors | M. Martínez Euklidiadas, Raquel C. Pico

According to the WHO, around 1.3 billion people in the world are affected by some form of visual impairment, of which at least 36 million are completely blind and 217 million have a moderate to severe visual impairment. Given that an increasing number of people are living in cities, it seems logical to facilitate the lives of people living with with visual impairment or blindness through accessibility.

Similarly, vision is one of the senses notably affected by the passage of time; it is quite common for visual acuity to decline with age. Although only a smaller percentage experience visual impairment severe enough to affect daily life, the Spanish Society of Geriatrics and Gerontology estimates that 30% of people over the age of 65 have some form of vision problem.

Therefore, just like other accessibility measures, the improvements cities make to simplify everyday tasks for individuals with visual impairments ultimately benefit everyone, as anyone may need these features at some point in life.

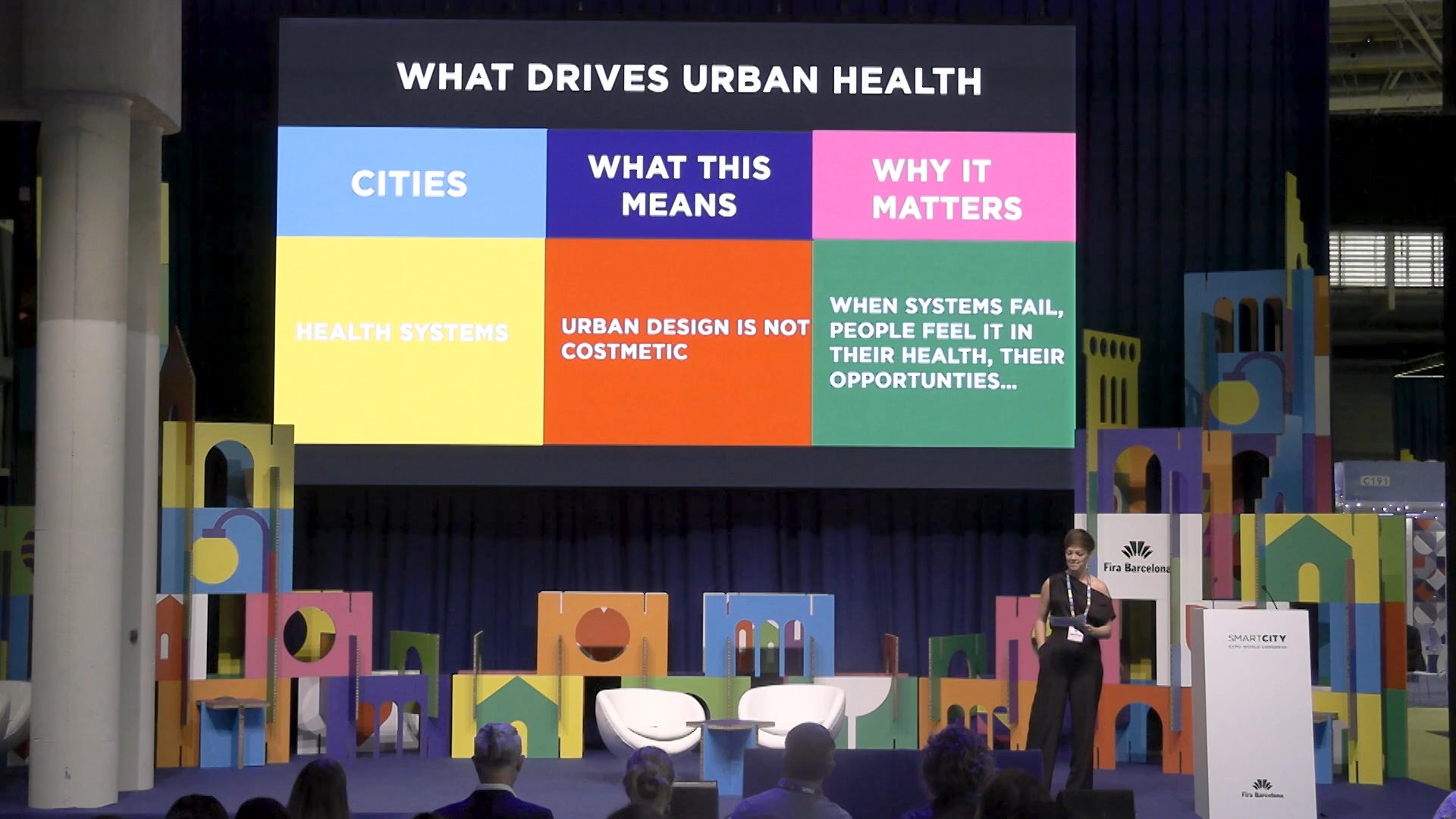

The importance of effective urban design

The key to making cities more accessible and improving the quality of life for residents with vision impairments lies in thoughtful urban planning and effective public policies. Of course, when developing public policies and accessibility strategies, it is important to recognize that visual impairment exists on a spectrum, and the range of needs is remarkably diverse. In other words, not all individuals are completely blind, and accessibility measures must be designed to accommodate the full range of visual abilities.

Cities must be designed with the goal of simplifying mobility, ensuring access to information and services, and enhancing livability for all residents. Singapore, recognized as the world’s most accessible city by a study by The Valuable 500, has adapted 95% of its zebra crossings and bus stops to be accessible for people with disabilities.

In the case of visual impairment, certain basic elements can help prevent mobility issues and enhance everyday life. Maintaining clean sidewalks and ensuring that elements like terraces or plant pots do not become obstacles is crucial, as are features such as tactile paving to guide the way. Additionally, adding auditory cues, like floor announcements in elevators or information about door movements, can make a significant difference. By adopting the principles of universal design, solutions are created that are inherently more inclusive and accessible to a global audience—ensuring that the message is clear and comprehensible to everyone, regardless of location, abilities, or circumstances.

A holistic urban strategy that recognizes accessibility as a fundamental necessity, rather than an added extra, is key to ensuring the quality of life for residents and fully leveraging the potential of smart technologies and urban design. For instance, urban data can reveal weaknesses and provide insights on how to address them.

What is smart technology and how can it help visually impaired people?

The Global Compact on Inclusive & Accessible Cities declaration, presented during the International Day of Persons with Disabilities (2019) and within the scope of the Cities for Everyone project —aligned with the New Urban Agenda or, the Sustainable Development Goals— is__ a global commitment to make cities more accessible.__

Technology plays an essential role in this commitment. In fact, it is imperative for smart cities to generate adapted technology to prevent it from becoming a barrier, since smart technology is technology that can be used by everyone.

As an example of bad use of technology, in 2016, the American Federation for the Blind sued New York City because the LinkNYC system, which offers Wi-Fi, charging points and a place in which to carry out procedures, was not only not adapted for visually impaired users, but it was in fact an architectural barrier.

Assistance for blind people in cities: tactile maps, orientation apps and other smart technologies

Historically, touch has played an important role in the integration of blind people. It is easy to find tactile tourist maps, sentences in braille format or tactile paving that guide people. However, technology is opening more possibilities and audio technology is set to become the next major revolution, combined with artificial intelligence.

The Google Lockout application is one of the tools being developed, which enable visual data detected by a smartphone camera to be transformed into audio format. This allows objects to be located, signs to be read and even to understand labels, although it will still take a few years for it to become a useful tool. Luckily, other urban tools are being deployed:

Bluetooth beacons for smart cities

The Wayfindr project is an open standard via which, the visually impaired can be guided through complex environments using a Bluetooth beacon system and 5G networks. Successfully tested in the London Underground system, this standard could become one of the main forms of navigation for visually-impaired and blind people, but also for any other user.

In Warsaw, Poland, these beacons are essential in empowering people with visual impairments to navigate the public transport network independently. Urban buses are equipped with these beacons, allowing people at bus stops to receive notifications on their smartphones when a bus is approaching the stop. This allows them to stay informed without relying on others to explain what is happening.

BART Maps (Tactile Mapping Project)

For years, tactile graphics have been the Holy Grail of urban maps for the visually impaired. However, they still need to improve much more, by integrating layers of audio or making them more accessible. That is the aim of the San Francisco Bay public transport Tactile Mapping Project, which has spent years designing a tactile and audio standard to represent the 44 stations in the region.

Lazarillo: navigate any city using an app

Lazarillo is an app for getting around any city. Aimed at navigation through audio, the app informs users of the street they are walking along, other nearby streets, the stores, services or transport available nearby or how to walk from one place in the city to another.

By definition, a smart city must take into account the different needs of its population. And this includes the elderly, people with difficulties in getting about, people with different levels of visual impairment, deafness and other disabilities affecting their autonomy. They also form an integral part of cities.

Success stories

Meanwhile, the digitalization of society is unlocking new opportunities to improve the quality of life for individuals with visual impairment. While artificial intelligence holds great promise for addressing future urban challenges, today’s technological tools are already demonstrating remarkable potential.

Smartphones have become essential tools, now owned by the majority of the population. Some pilot initiatives are testing their potential as a means to improve accessibility in urban environments. In Taiwan, smartphones have been tested as tools to assist people with visual impairments in safely crossing streets. Meanwhile, in Dubai, an iPhone app was trialed to translate all written information in the metro network into audible messages.

A prime example of how a city can evolve to become more inclusive for its visually impaired population is Marburg, Germany, often referred to as ‘Blindenstadt’ (a city designed for blind and visually impaired people, as highlighted by the BBC).

Since the early 20th century, Marburg has been home to the Blindenstudienanstalt, an education center for blind people. This institution has fostered a longstanding tradition of awareness around the accessibility needs of this population, transforming the medieval city into a model of accessibility. The city’s buildings feature tactile maps, traffic lights and bus stops are equipped with sound signals, restaurant menus are available in Braille, and customer service staff are trained to assist and provide information to blind individuals. In fact, its accessibility is one of its strongest selling points and a key aspect of its urban identity.

Images | iStock/Halfpoint, CDC