Author | M. Martínez Euklidiadas

Venice is gradually sinking. It has been sinking for many centuries and will continue descending into the lagoon over the next millennia. In addition to the historical causes due to the lack of effective land support systems (technically, ‘subsidence’), is the increase in water levels as a result of man-made climate change.

The Venice canals are steadily covering more windows. A recent study by Italy’s National Institute of Geophysics and Volcanology (INGV) predicts that Venice will be completely submerged by the year 2150.

A 2021 report by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) predicted that the average regional sea level will rise by 28 to 55 centimeters by 2100 under the most optimistic global warming scenarios, and by 63 to 101 centimeters under the most pessimistic scenarios

Initiatives such as the MOSE system (MOdulo Sperimentale Elettromeccanico), based on a system of hydraulic floodgates, have helped prevent the rising sea levels from reaching the lagoon in the past. However, these measures designed last century in the 70s, are completely insufficient in terms of combating the rising levels of the Adriatic Sea today. Does Venice have a future?

Venice today: Why is Venice under water?

The ancient city of Venice (Venice, Murano and Burano) was built on a few hundred small islands in the Venetian Lagoon, with their buildings supported on timber piles, as the population of fishermen moved to the islands in search of protection from the invasion of the Huns and Lombards. Today it is a tourist attraction thanks to its water canals.

Over almost a millennium, those piles have been sinking into the lagoon bed, leading to land ‘subsidence’ at a rate of between 2 and 4 centimeters each century. Unfortunately, the extraction of water from the aquifers through artisan wells during the 50s and 60s, combined with the rise of the Adriatic sea levels during the 20th century due to the Mediterranean temperature increase, have accelerated this rise.

According to the IPCC, sea water levels rose between 10 and 25 centimeters and by 2100 they are expected to rise between 60 and 110 centimeters. Both factors, land subsidence and rising sea levels, are inevitable in centuries to come, and they are leading to the city of Venice sinking even further each time the tides rise, which is occurring increasingly often.

Does Venice flood very often?

High tides are known in the city as Acqua Alta (high water), and they are not new. What is new is how often these water rises occur. The touristic Saint Mark’s Basilica, consecrated in 1094 in the square with the same name, is being flooded more than ever.

At the end of 2019, flooding that reached 1.87 meters submerged more than 80% of Venice and resulted in damages amounting to 1 billion euros. The consequences were devastating and long-lasting, causing serious damage to the marble and other architectural elements of Venice’s historic buildings.

Economically speaking, current efforts to address the damage caused by the flooding in Venice include the restoration of Saint Mark’s Basilica, valued at 3.3 million euros.

At the end of 2019, a flood peaking at 1.87 meters seriously damaged the marble and other architectural elements. Some witnesses even spoke of waves in St. Mark’s Square. The graph below, with figures from 1872 to 2020, indicate that future high tides will be much worse than previous ones.

In Venice, high tides are most frequently recorded in November and December. Although they only last a few hours, their intensity varies depending on the district. Districts located in the lower parts of the city, such as the aforementioned Saint Mark’s Square or around Dorsoduro, are the most affected, while higher areas like Cannaregio generally do not experience significant water or flooding issues.

Given the rapid nature of the tides, the Venetian authorities warn residents via telephone or SMS. If a particularly severe tide is expected, a siren system located across the island is activated

Can Venice be saved from sinking or is it condemned?

In the long term, in centuries or even millennia to come, the ancient city of Venice will be devoured by the lagoon, as has been the case with other similar cities throughout history, Tenochtitlan in the past and Jakarta today.

Saving Venice is a technical issue, and therefore, financial. The technology required to replace every wooden pile in the city with longer ones is available and the entire city could even be moved in the same way as dozens of Egyptian temples.

However, both projects would require a continuous supply of funds that would be much higher than those provided for the existing projects, which are already extremely costly. But when these funds are no longer available and the capital stops flowing, Venice will fall. Recent figures indicate that this happen even with systems like MOSE.

MOSE Venice’s floodgate system: What is its purpose?

With the aim of interrupting the rising level of the Venetian Lagoon each time water is pushed in from the Adriatic Sea, the MOSE system was designed to be a physical barrier between both bodies of water. Built in 2003 and expected to be completed in 2021, it was first used in October 2020, relatively successfully.

Its 78 mobile barriers were activated early in the morning on October 15, after the tide was forecast to reach 135 cm. Without the barrier, tides of this magnitude would have flooded half of Venice.

By mid-morning, strong winds and rain had already caused sea levels to rise to 140 cm in some parts of the lagoon. However, within the city of Venice, the water level remained stable between 50 and 60 cm, thus staying within safe limits.

How does the MOSE system work?

The MOSE system consists of 78 retractable mobile floodgates that are raised up to block the high tides of the Adriatic Sea. Installed in the Venetian Lagoon’s three mouths connecting with the Adriatic Sea where the sea level rises, the water is extracted from inside these adjustable walls, making them rise with the pressure of the sea and blocking the passage of water from the Adriatic Sea to the lagoon.

How much does the MOSE system cost?

Although initially the project was going to cost 3.2 billion Italian Lira in 1989 (around 1.6 billion euros), the reality is that the cost has gradually increased. It has not helped that the five decades of the project have been marred by corruption, tax fraud and unlawful financing policies.

In 2013, before the project began, 4.9 billion euros were made available, however, one year after the budget, it had risen to 5.3 billion euros. In November 2019, the project was 94% complete and its cost had exceeded 5.5 billion euros, without taking into account future annual maintenance costs. As of 2024, the costs have continued to rise, surpassing 6 billion euros, according to this study.

Was the MOSE system completed?

While the initial estimate for the completion of the system was set for 2021, new projections now indicate it will be finished by 2025. The Malamocco barrier, located in the deepest section, requires three more years and is expected to be completed by the end of 2024. In contrast, the barriers at Lido and Chioggia were projected to be finished by the end of 2023.

These delays have been caused by obstacles such as corruption and increased costs. The greatest delay, however, is due to errors in the design and execution phases, along with anomalies and malfunctions such as rust and other forms of erosion.

The interventions enabled by new funding of 538 million euros will require an additional four years from the time they were granted, with completion expected by December 2025.

There are serious doubts regarding whether the MOSE system will be capable of tackling future rises in the Adriatic Sea levels (see graph above). As the tides are increasingly frequent and high, these floodgates are expected to function as a permanent wall.

In addition to the current environmental impact of the construction and maintenance of the system, is the non-evacuation of contaminants from the lagoon, which could become a body of water like the Spanish Mar Menor, one of the most contaminated bodies of water in Europe. Various articles in Nature are already warning that these floodgates could destroy the lagoon’s fragile ecosystem.

The Netherlands, which is dangerously below sea level, may serve as an example for Venice. A Dutch-style solution for Venice would involve implementing plans similar to the Delta Project, an enormous flood management system comprising 13 dams and numerous dikes, barriers, and sluice gates, which have been in operation since 1997.

According to the Watersnoodmuseum, a museum dedicated to flooding, this solution is so effective that the region protected by the Delta Project is estimated to flood only once every 4,000 years.

However, Venice is running out of time, and the Dutch example is far from being a quick solution. The Delta Project took nearly 50 years to complete and is incredibly intricate. The total length of the Delta Project dams is 30 km, which is 18 times longer than MOSE.

Images | @canmandawe, Egor Gordeev, Città di Venezia, Irønie

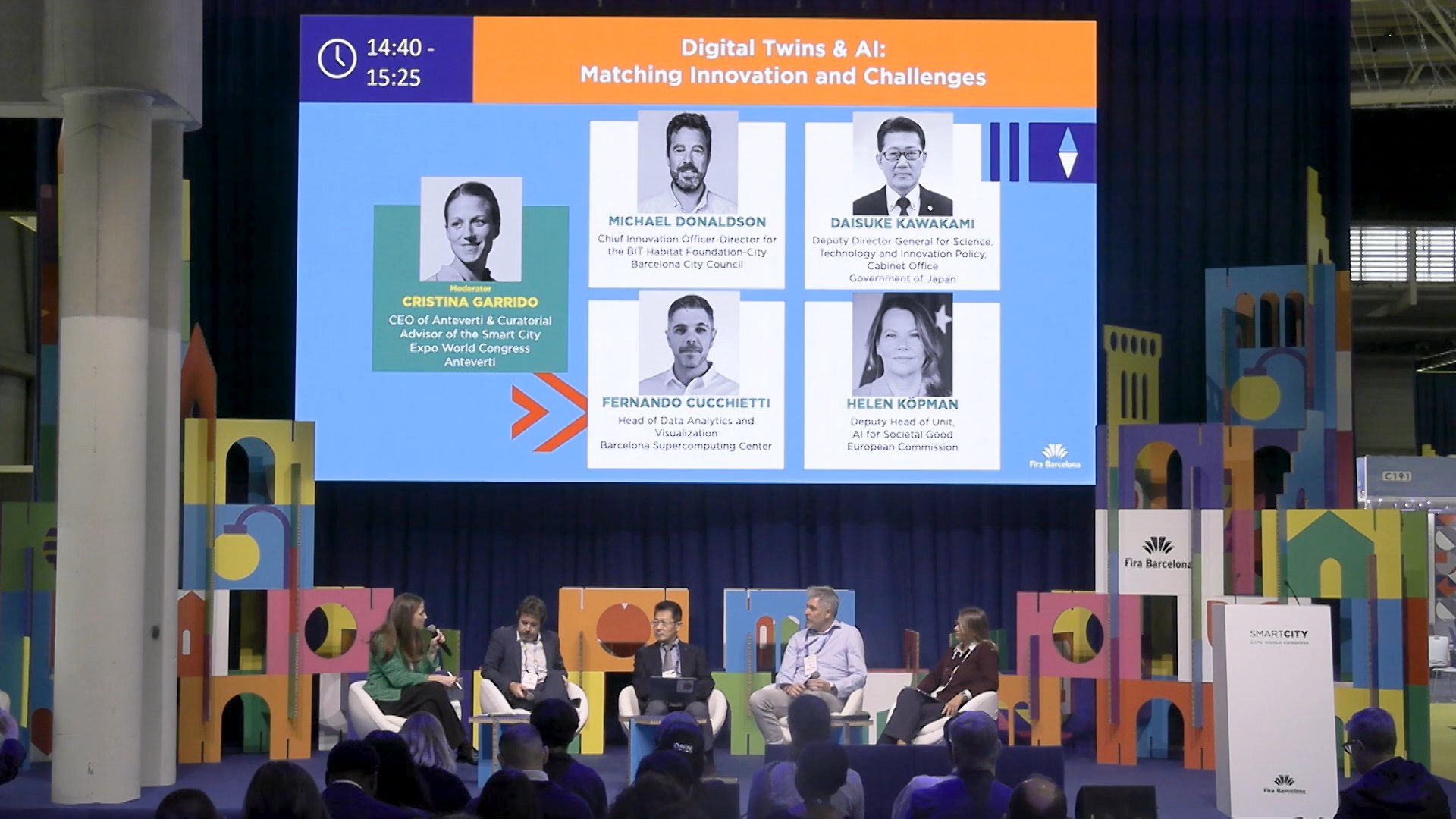

Tomorrow.Building World Congress (5-7 November 2024, Barcelona) is the new global event empowering the green and digital transition of buildings and urban infrastructures. Celebrated in parallel with the Smart City Expo, it’s a sector-focused summit gathering the most forward-thinking brands and experts disrupting urban construction. Discover more here.