Authors | Jaime Ramos, Raquel C. Pîco

Birth rate is now a hot topic across the world. This is due to the declining rates in Western nations as well as the exponential population growth in the rest of the world. This particularly affects cities, which already hold 54% of the world’s population, a proportion which is expected to increase to 66% by 2050.

The decline in birth rates has emerged as a prevalent trend across nearly all economies in recent years. In fact, recent studies suggest that the global fertility rate has decreased significantly, dropping from 4.8 children recorded in 1950 to 2.2 today. Analysts are increasingly concerned about the future, predicting significant challenges in the coming decades as birth rates decline in developing countries, fail to recover in developed nations, and the global birth rate is projected to fall further to 1.8 children by 2050.

The decline in birth rates, along with the potential decrease in the global population, can be attributed to a variety of factors. Gender inequality and the professional penalties often associated with motherhood significantly influence birth rates. Additionally, economic precariousness and uncertainty further contribute to this demographic shift.

Fairness in maternity

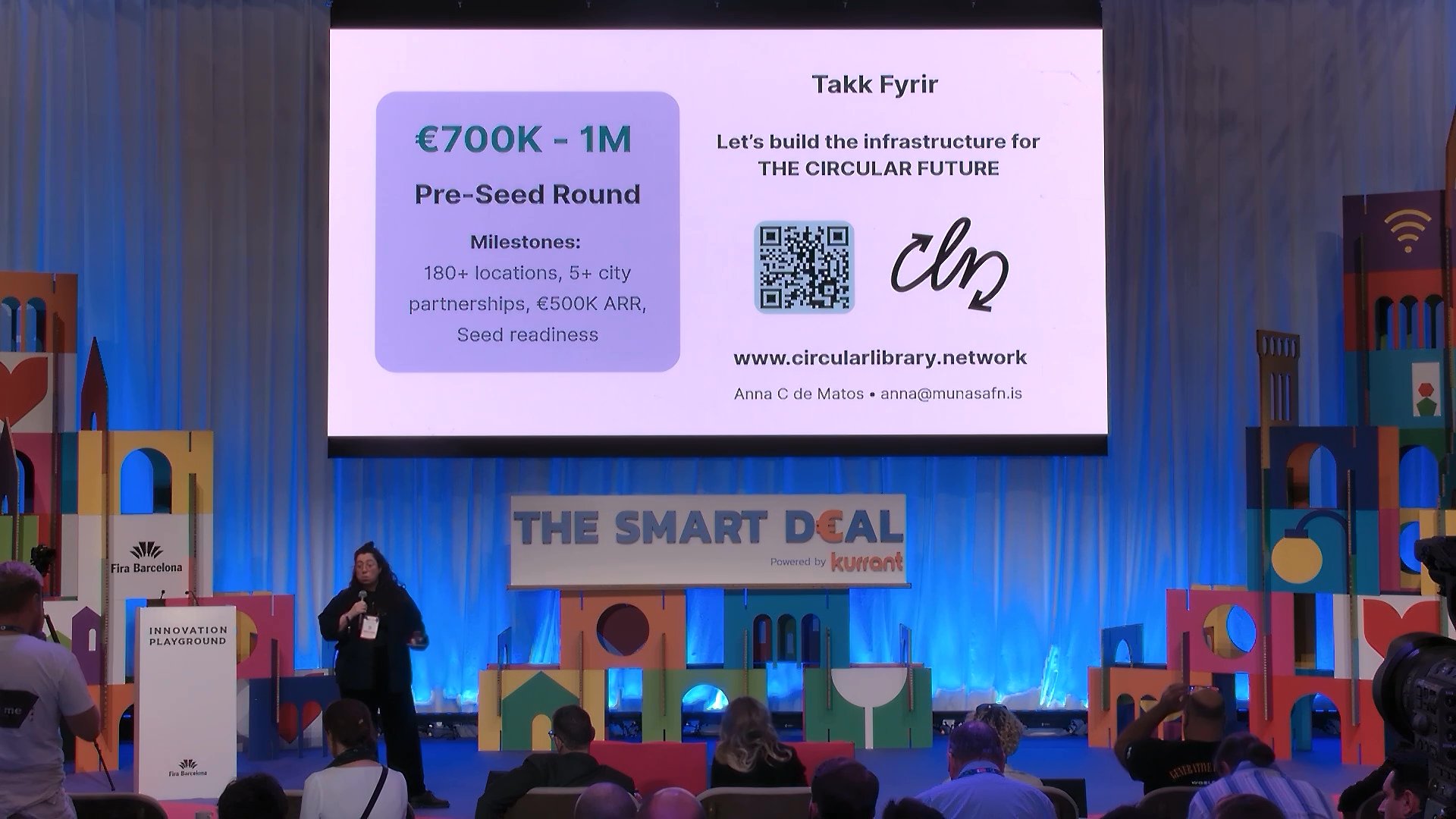

These situations generate strong social differences, which are experienced even before a child is born. This is also a challenge faced by smart cities, which involves taking steps to ensure fairer conditions in terms of maternity and paternity.

Urban planning with a commitment to the family as the original nucleus of society begins with equal access to healthcare. This is an extraordinary challenge in countries with large populations and high birth rates. At the other extreme, in points of the globe where birth rates are declining and the population is ageing, smart cities are developing formulas to integrate families with new members into their structures and encourage this to occur.

Combating child mortality

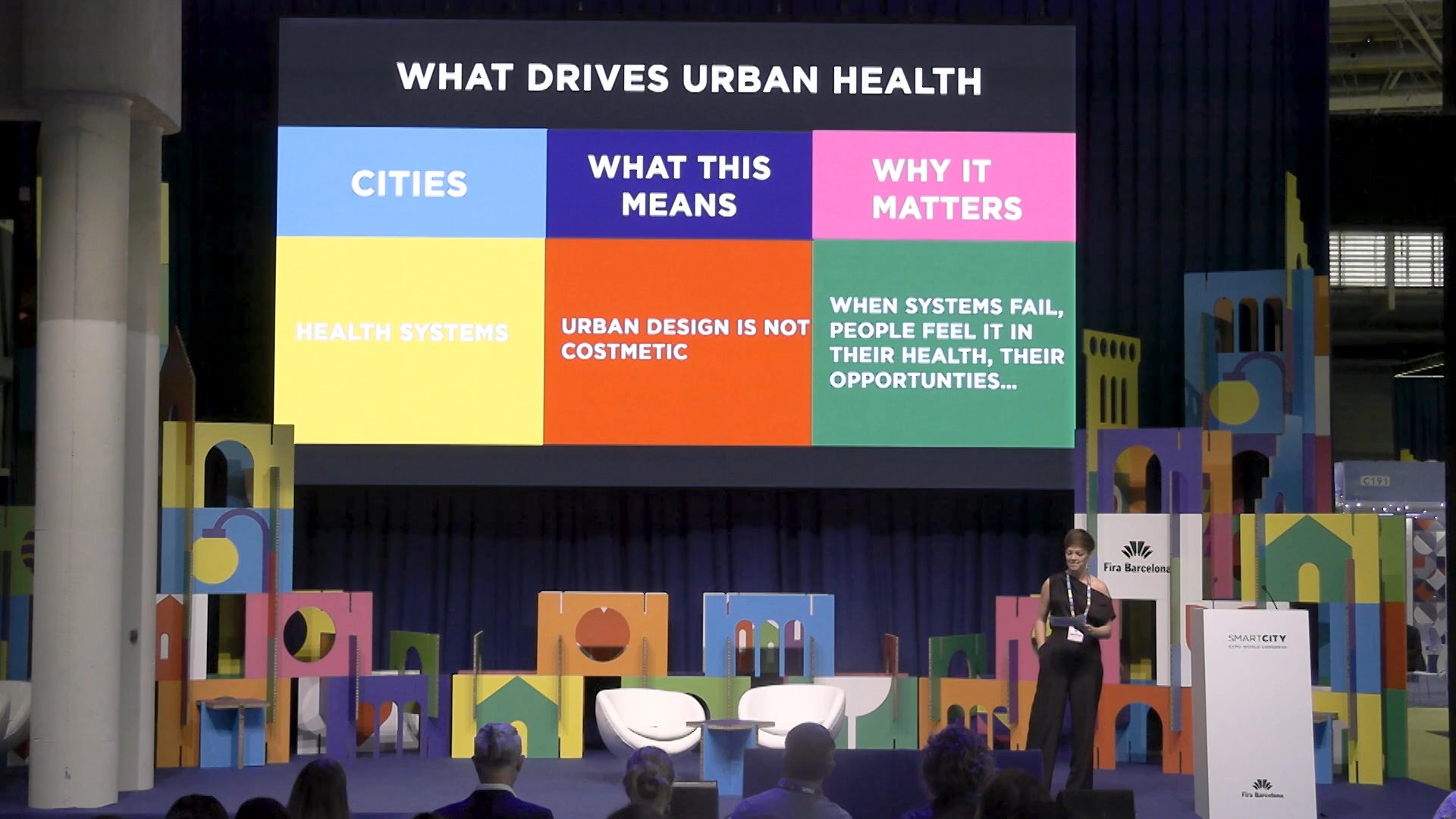

Likewise, child mortality and maternal mortality remain critical issues, posing significant challenges that continue to affect populations globally. Addressing global child mortality rates demands a multifaceted approach, as the figures vary significantly across different countries and regions.

In general, and according to World Health Organization (WHO) data, child mortality rates have been steadily declining since the 1990s. Between 1990 and 2022, deaths of children under the age of five have decreased by 59%, falling from 12.8 million to 4.9 million. Despite this, the WHO indicates that neonatal deaths have declined at a slower pace. As of 2022, approximately 6,300 newborns still die each day worldwide. Furthermore, child mortality rates have plateaued since 2015.

Where you are born continues to play a decisive role in determining chances of survival. According to the WHO, a newborn in sub-Saharan Africa is 11 times more likely to die within the first month of life compared to a newborn in Australia or New Zealand. Although survival figures are much more positive in more developed countries, where there are extensive health resources, things are not perfect there either. In some cases, mortality rates at birth and during the subsequent months for both babies and mothers remain too high. Maternity and pregnancy continue to be processes fraught with significant risks.

A particularly paradoxical example can be found in the United States. This powerful country has an excessive child mortality rate. There are 5.8 infant deaths for every 1,000 births the US. This public health problem is due, in part, to the social gaps still existing in the country.More specifically, black babies are 2.4 times more likely to die than white babies. In this regard, this year, the city of Columbus, in Ohio, will test a pilot programme to assist pregnant women, in a bid to tackle the problem of the number of infants dying within the first year of life.Aimed at the most disadvantaged areas, the project will connect and monitor pregnant women providing them with transportation for healthcare and other essential services such as grocery shopping or pharmacy trips.

Improving breastfeeding and complementary feeding practices

Another project in the same vein is Alive and Thrive, which seeks to extend the benefits of maternal breastfeeding worldwide. Funded by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, together with the government of Canada and Ireland, it understands that breastfeeding is an investment, not just for the health of babies, but for society as a whole.

They indicate that each dollar invested in breastfeeding generates a return of $35 to society in economic benefits, by improving children’s health and thanks to the benefits in terms of cognitive development. In this regard, smart cities are equipped with resources to integrate breastfeeding as a beneficial social phenomenon.

Recently, there has been a surge in solutions to help mothers to begin breastfeeding or prevent early weaning. An example of this is Momsense. This is a sensor-based system designed to analyse how babies breastfeed.

Cities play a crucial role in ensuring that maternity, pregnancy, and child-rearing are healthier and safer experiences. Urban planning can promote solutions to address many challenges hindering birth rates while making life easier for families. It is also essential to recognize that the concept of family has evolved significantly over the decades, becoming much more diverse.

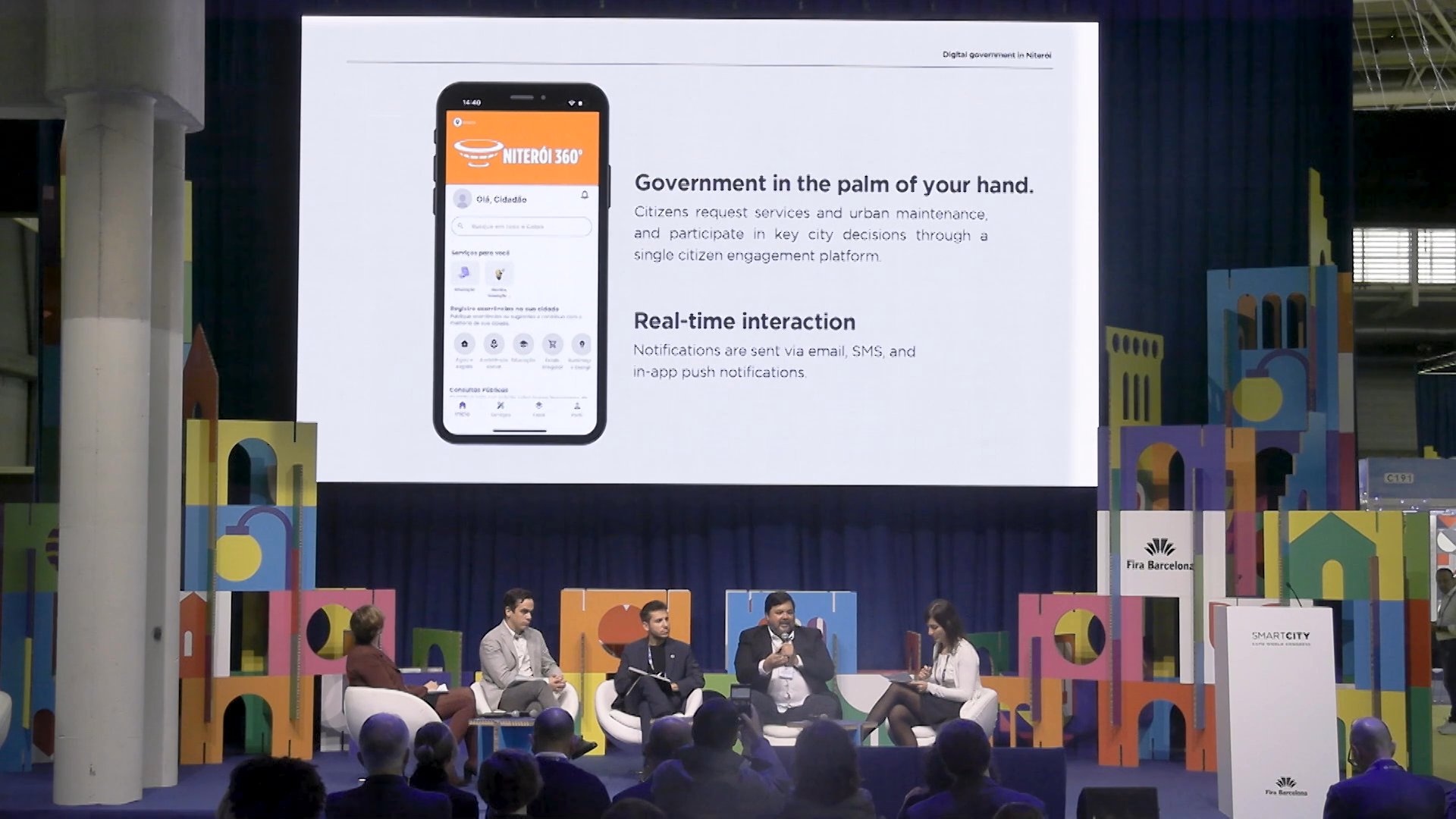

In more developed countries, the challenges of paternity, maternity and breastfeeding, are closely related to employment conditions. For working mothers, it is really complicated to reconcile their work with breastfeeding. In this respect, smart cities provide solutions such as teleworking and flexible working schedules.

Urban design and architecture can play a role in supporting breastfeeding by creating more inclusive and accessible spaces for breastfeeding. Breastfeeding rooms provide comfortable, clean, and private spaces for mothers to feed their babies. Even so, these solutions cannot obscure the broader challenges that make child-rearing a journey fraught with obstacles, such as the persistent stigma surrounding breastfeeding in public. In the European Union, discrimination against women during the breastfeeding period is prohibited, ensuring that mothers have the right to breastfeed without facing legal restrictions. However, in some regions, regulations still prohibit breastfeeding in public spaces.

It is also crucial to consider a range of other factors when designing cities to make them more conducive to raising children. For instance, something as straightforward as ensuring support services are not restricted by gender—such as including baby-changing facilities in all restrooms, not just those for women—helps promote awareness that parenting is a shared responsibility. This approach not only fosters greater involvement from fathers but also contributes to reducing gender disparities.

We cannot ignore the significant social and economic benefits of overcoming these current obstacles, nor the fact that harmonising birth rates and helping parents may pose significant problems regardless of the wealth of the cities.

Images | iStock/petrenkod, iStock/tatyana_tomsickova, iStock/lolostock, Olivia Bauso